Black and White Dreams: The Giver

My loves! I’m terribly apologetic for how late this post is: I had some posting difficulties to over come! But now we’re here, let’s have a look at The Giver and how colour and culture give rise to revolutions (or whatever).

So we’ve had the delight of thumbing through The Giver for the first, or fifteenth time and now we’re looking to talk about all the elements we love and hate and think about the most. What struck me most clearly on this read of the novel is the use of colour and how it pushes the narrative forward.

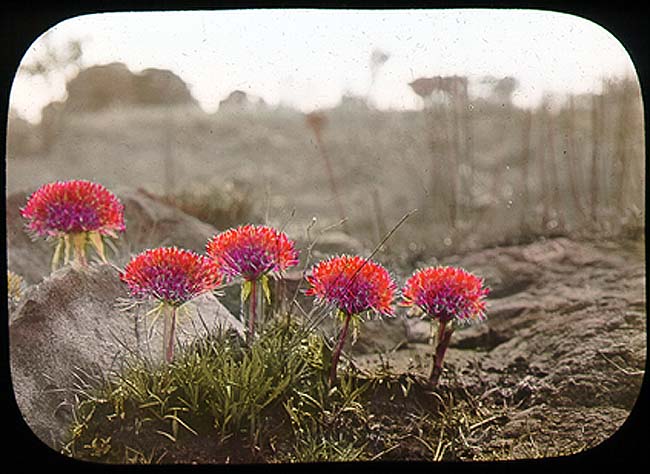

The first colour Jonas sees is red, and this is the underlying manifestation of his destiny as a Receiver. There’s something mildly concerning about the fact that his first memory is of red – it’s a symbolically rich colour, whether for love, lust or death. The beauty of Lowry’s description of the apple mid air and the stunning quality of Jonas’ secret(ish) crush are well worth reading more than once. While Lowry maintains a considered and generally simple writing style, there is nothing lacking in the atmosphere for the situations that arise. The increasing glimpses of colour, and the introduction of further sensations as we read through the chapters mirror Jonas’ personal development across the span of a year in the Giver’s presence. We learn and feel alongside Jonas as he begins to very firmly question the life his community lives and ultimately to revolt.

In this totalitarian society we realise very quickly that things aren’t quite right. Life is regulated within an inch and there is a clear focus on conforming to the whole. Do texts like this, with clear agendas regarding political concepts, intend to make us as readers more aware of what’s going on in our own societies? Or is this text just an interesting glimpse into a world that we will never actually experience? Do we really believe that hundreds of years from now governments will have the ability to remove even our concept of colour from our consciousness? or are we rather concerned that regulations and rules “for the greater good” might go so far out of hand that we don’t even realise when things are going pear shaped. Running along the same political lines as writers such as George Orwell, Lowry’s novel is less static and instead involves the reader directly in the problem using engaging description and rhetoric. We spend an awful lot of time being told what is going on and why through the journal-esque nature of the narration.

One thing that the novel does seem to have a fairly positive spin on is that women are not downtrodden. They cover the same jobs as men, and find these appointments based completely on their own desires and skill. Of course there’s a lot of negativity around birth mothers, this is offset by the children’s thoughts regarding the occupation. The Big Brother feeling to the community is doubled when we learn that the elders have been watching the children for some time, and no doubt have extensive notes on them all. This exposition takes time and I do sometimes feel that there is a lack of speed to the novel, and I am trudging though some pretty obvious info dumping. This doesn’t happen all the time, but it does get in the way of an otherwise very enjoyable narrative.

Some friendly questions for you all to consider;

Did you enjoy the novel?

Would you have left the community?

And what do you think of the Giver’s lack of initiative even after his own daughter dies for the community?

Which sensation would you most miss, if you were in the community?

Does the totalitarian nature of such (ultimately dystopian) texts cause concern for the world in it’s current state?

I adore The Giver, and one of the most interesting things about it to me is the fact that people keep trying to get it banned. Many parents think it’s far too complex for children to understand, and that it will lead them to disobey adults and go against the rules set out for them. Not surprising at all, children are able to come to a much deeper and fulfilling understanding of this excellent novel.

Dystopian texts are often though to spell horror for our current state (lol) but are really a by-product of paranoia that already exists. When wars or other political conflicts are going on, or we hit an economic dip, or people feel their rights are being infringed this type of fiction becomes popular again. Writers don’t (usually) think this stuff will actually happen, but they write it and people read it because deep down we’re all a little paranoid.